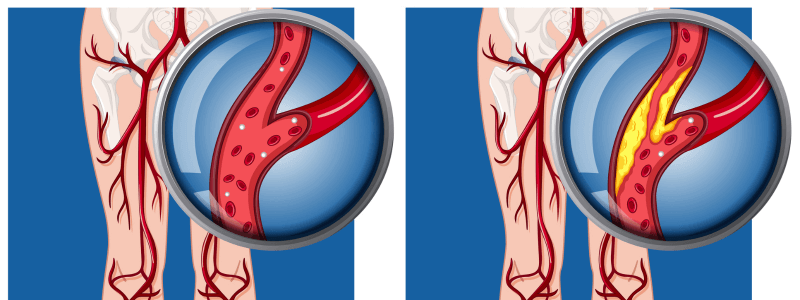

Acute limb ischaemia is defined as a sudden decrease in limb perfusion that threatens the viability of the limb. It is most commonly caused by acute thrombotic occlusion of a previously partially occluded, thrombosed arterial segment or secondary to an embolus from a distant site. It is a surgical emergency, and without surgical revascularisation, complete acute ischaemia results in extensive tissue necrosis within six hours.

Aetiology

The most common cause of acute limb ischaemia is acute thrombotic occlusion of a pre-existing stenotic arterial segment (60% of cases). The second commonest cause is embolism (30%), e.g., from left atrial thrombus in patients with atrial fibrillation (accounts for 80% of peripheral emboli), mural thrombus following myocardial infarction, or from prosthetic heart valves. Distinguishing these two conditions is important because treatment and prognosis are different.

Other causes include:

- Trauma

- Raynaud’s syndrome

- Iatrogenic injury

- Popliteal aneurysm

- Aortic dissection

- Compartment syndrome

Clinical features

The typical features of acute limb ischaemia are classically described using the ‘6 Ps’:

- Pain (constantly present and persistent)

- Pulseless (ankle pulses are always absent

- Pallor (or cyanosis or mottling)

- Power loss or paralysis

- Paraesthesia or reduced sensation or numbness

- Perishing with cold

Differentiating between ischaemia due to a thrombus and ischaemia due to an embolus

It is important to be able to differentiate between ischaemia due to a thrombus and ischaemia due to an embolus. The following table highlights the main differentiating features:

| Embolus | Thrombus |

|---|---|

| Onset acute (over seconds to minutes) | Onset insidious (over hours to days) |

| Ischaemia is usually profound (because there is no collateral circulation) | Ischaemia is less severe (due to collateral circulation) |

| There is not usually a history of claudication, and pulses are usually present in the other leg | There will often be a history of claudication, and pulses in the other leg may also be absent |

| Skin changes of the feet (such as marbling) may be visible. This can be a fine reticular blanching or mottling in the early stages, progressing to coarse, fixed mottling | Skin changes usually absent |

Investigations

All patients with suspected acute limb ischaemia should have an ankle brachial pressure index (ABPI) performed. This provides an index of vessel competency by measuring the ratio of systolic blood pressure at the ankle to that in the arm, with a value of 1 being normal.

An ABPI ratio of:

- Less than 0.5 suggests severe arterial disease

- Greater than 0.5 to less than 0.8 suggests the presence of arterial disease or mixed arterial/venous disease

- Between 0.8 and 1.3 suggests no evidence of significant arterial disease

- Greater than 1.3 may suggest the presence of arterial calcification, such as in some people with diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, systemic vasculitis, atherosclerotic disease, and advanced chronic renal failure.

Other important investigations to arrange include:

- Hand-held Doppler ultrasound scan to look for any residual arterial flow

- Blood tests – FBC, ESR, blood glucose, thrombophilia screen

- If the diagnosis is in doubt, perform urgent arteriography.

Investigations to identify the source of an embolus include:

- ECG

- Echocardiogram

- Aortic ultrasound

- Popliteal and femoral artery ultrasound.

Management

If acute limb ischaemia is suspected, an emergency assessment by a vascular surgeon should be arranged. Secondary care management will depend on the type of occlusion (thrombosis or embolus), location, duration of ischaemia, co-morbidities, type of conduit (artery or graft), the risks of treatment, and the viability of the limb.

Interventions include:

- Percutaneous catheter-directed thrombolytic therapy

- Surgical embolectomy

- Endovascular revascularisation if the limb is viable

- Revascularisation if the limb is marginally or immediately threatened – whether a surgical or endovascular technique is more appropriate will depend on a number of factors, including time to revascularisation and the severity of sensory and motor deficits.

- Amputation if the limb is unsalvageable (as the revascularisation of an irreversibly ischaemic limb with extensive muscle necrosis can lead to reperfusion syndrome from the release of inflammatory mediators and result in multiorgan damage and death).

Header image used on licence from Shutterstock

Thank you to the joint editorial team of www.mrcemexamprep.net for this article.

Good article , nicely explained