The menstrual cycle is the regular cycle of vaginal blood loss (menstruation) that results from the breakdown of the uterine lining when the implantation of a fertilised ovum does not occur.

Menstruation occurs on a monthly cycle throughout a woman’s reproductive life. The onset is menstruation (menarche), usually occurs between the ages of 11 and 15 (mean age 13.3 years) and the end of the menstrual cycle (menopause) between the ages of 45 and 55 (mean age 51).

The usual duration of a single cycle is between 21-35 days. Average menstrual blood loss is approximately 25 ml per day for 4 to 5 days per month.

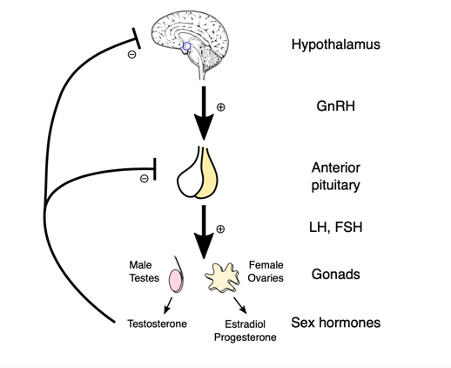

The hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis

The menstrual cycle is regulated by the hormones of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis. The hypothalamus releases gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH), which in turn stimulates the release of the gonadotropin hormones luteinising hormone (LH) and follicular-stimulating hormone (FSH) from the anterior pituitary gland.

LH stimulates the theca cells in the ovary to produce and secrete androgens, which are subsequently converted into oestrogen by adjacent granulosa cells. FSH binds to the granulosa cells to permit the conversion of androgens to oestrogens, stimulate follicle growth and stimulate inhibin secretion.

The production of LH and FSH is controlled by a feedback system that is primarily regulated by GnRH. Negative feedback is exerted on the HPG axis by moderate oestrogen levels, but high oestrogen levels in the absence of progesterone exert positive feedback. Oestrogen and progesterone together exert negative feedback on the HPG axis. The production of inhibin selectively inhibits the secretion of FSH from the anterior pituitary.

This hormonal feedback system results in two separate cycles occurring interact and overlap: the ovarian and the uterine cycles.

The HPG axis, image sourced from Wikipedia

Courtesy of Artoria2e5 CC BY-SA 3.0

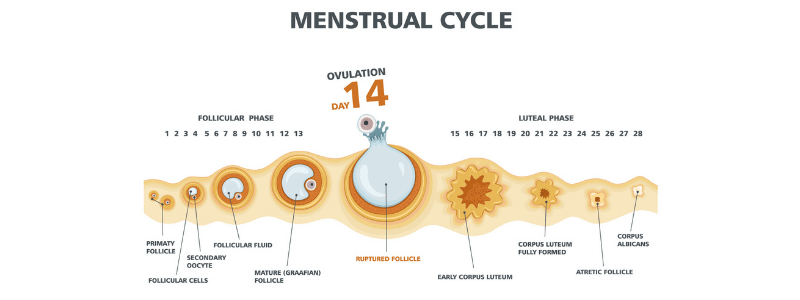

The ovarian cycle

The ovarian cycle describes the changes that occur in the follicles of the ovary. It has three phases:

- The follicular phase

- Ovulation

- The luteal phase

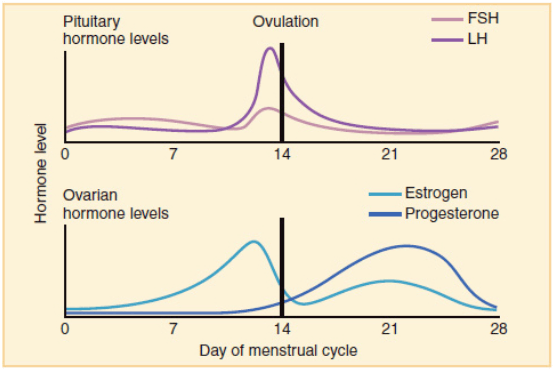

The follicular phase is the first part of the ovarian cycle. During this phase, the ovarian follicles mature and prepare to release an egg. At the onset of a new cycle, sex steroid and inhibin levels are low, resulting in minimal negative feedback on the HPG axis. This results in a rise in the production of GnRH and increased LH and FSH levels which, in turn, stimulate follicle growth and oestrogen production. The follicular cells become luteinised at this point and express receptors for LH. The follicles compete with others for dominance, but only one continues to maturity and completes each menstrual cycle. The follicle that reaches maturity is called the Graafian follicle, and it contains the ovum.

Rising oestrogen levels initially exert negative feedback on the HPG axis, reducing FSH levels. However, follicular oestrogen levels subsequently rise to a high enough level to initiate positive feedback at the HPG axis, increasing GnRH and gonadotropin levels. Inhibin selectively suppresses FSH production; therefore, only LH levels rise, which is referred to as the ‘LH surge’.

In response to the LH surge, the ovarian follicle ruptures and the mature oocyte is released from the Graafian follicle into the oviduct. This marks the start of the ovulation phase of the ovarian cycle. The oocyte is assisted into the fallopian tube by fimbria, where it remains in a state viable for fertilisation for approximately 24 hours. Once the oocyte has entered the fallopian tube, it is referred to as the ovum.

After ovulation has occurred, the ruptured follicle closes and forms the corpus luteum, marking the start of the luteal phase of the ovarian cycle. The corpus luteum produces progesterone, which is now present in combination with oestrogen. This results in the exertion of negative feedback on the HPG axis, stalling the cycle in anticipation of fertilisation. In the absence of fertilisation, the corpus luteum spontaneously regresses after 14 days. There is then a fall in the levels of the sex hormones, ending the negative feedback on the hypothalamus. This resets the HPG axis allowing the ovarian cycle to begin again.

If fertilisation occurs, an epithelial covering of highly vascular embryonic placental villi called the syncytiotrophoblast invades the uterus to establish nutrient circulation between the embryo and the mother. The syncytiotrophoblast produces human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG), which exerts a luteinising effect that maintains the corpus luteum. It is supported by placental hCG, and it produces hormones to support the pregnancy. At around four months of gestation, the placenta is capable of production of sufficient steroid hormone to control the HPG axis itself.

Overview of the hormonal changes during the ovarian cycle, image adapted from Wikipedia

Courtesy of OpenStax College CC BY-SA 3.0

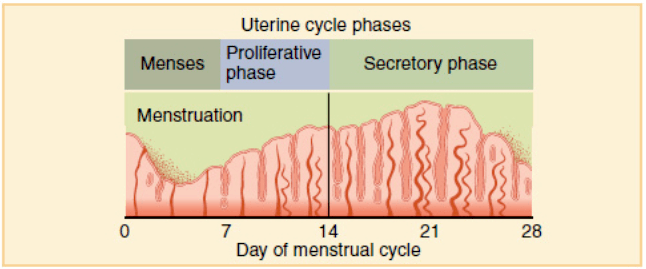

The uterine cycle

The uterine cycle describes the changes that occur in the endometrial lining of the uterus. Like the ovarian cycle, it has three phases:

- Proliferative phase

- Secretory phase

- Menstrual phase

The proliferative phase occurs simultaneously with the follicular phase of the ovarian cycle, preparing the reproductive tract for fertilisation and implantation. During this phase, the endometrium is exposed to increasing levels of oestrogen due to increased levels of LH and FSH. Oestrogen stimulates growth and repair of the functional endometrial layer, allowing recovery from recent menstruation. In addition, oestrogen initiates fallopian tube formation, increased growth and motility of the myometrium and production of a thin alkaline cervical mucus that facilitates the transport of sperm.

The secretory phase occurs simultaneously with the luteal phase of the ovarian cycle, commencing once ovulation has occurred. This phase is driven by the progesterone being produced by the corpus luteum. The increased progesterone levels stimulate further thickening of the endometrium into a glandular secretory form that makes the uterus a more welcoming environment for implantation. In addition, there is a thickening of the myometrium, reduction of motility of the myometrium, and the production of a thick, acidic cervical mucus production that creates a hostile environment that prevents polyspermy.

At the end of the luteal phase, in the absence of fertilisation, the corpus luteum degenerates. The loss of the corpus luteum results in decreased progesterone production, which causes the spiral arteries in the functional endometrium to contract. This loss of blood supply causes the functional endometrium to become ischaemic and necrotic. This results in the internal lining of the uterus being shed. Menstrual bleeding usually lasts between 2 and 7 days, with a total of between 10 to 80 ml of blood being lost.

Overview of the phases of the uterine cycle, image adapted from Wikipedia

Courtesy of OpenStax College CC BY-SA 3.0

Abnormalities of the menstrual cycle

There are several abnormalities of the menstrual cycle that can occur. These include:

- Menorrhagia – which is defined as excessive menstrual blood loss which interferes with a woman’s physical, social, emotional and/or material quality of life. Generally speaking, loss of greater than 80 ml per menses is considered to be menorrhagia, and over time, this can result in iron-deficiency anaemia.

- Dysmenorrhoea – which is defined as painful cramping, usually in the lower abdomen, which occurs shortly before or during menstruation, or both.

- Premenstrual syndrome – the symptoms women can experience in the weeks before their period, the most common of which are mood swings, anxiety, irritability, bloating, abdominal pain, headaches, and acne development.

- Abnormalities of timing – periods can occur too frequently (polymenorrhoea), too infrequently (oligomenorrhoea), or not at all (amenorrhoea).

- Abnormalities of onset of periods – onset before 8 years of age is considered to be precocious puberty, and onset after 15 years of age is considered to be delayed puberty.

Header image used on licence from Shutterstock

Thank you to the joint editorial team of www.mrcgpexamprep.co.uk for this article.