Tuberculosis is a disease caused by infection with the bacterium Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Approximately 10 million per year develop tuberculosis globally, and an estimated 1.7 billion people have latent tuberculosis. It is the second most common cause of death from an infectious disease worldwide after HIV/AIDS.

Mycobacteria tuberculosis is an obligate pathogenic bacteria of the Mycobacteriaceae family. It contains a lipid-rich cell wall that renders it impervious to Gram-staining and decolourisation with acid (acid-fast).

It is spread from person-to-person by the aerosol route, and the lung is the first site of infection. It primarily affects the lungs but can also affect several other parts of the body. It is most common in infants and children and has the highest prevalence in children under five years of age.

Primary tuberculosis

The primary infection is usually asymptomatic, and although it is possible to develop post-primary tuberculosis soon after transmission occurs, most cases arise from latent tuberculosis infection.

Latent tuberculosis infection is a state of persistent immune response to stimulation by Mycobacterium tuberculosis antigens without evidence of clinically manifested active tuberculosis. People with latent tuberculosis are not infectious and cannot transmit the infection to others.

Only around 5-10% of patients with latent tuberculosis go on to develop post-primary tuberculosis. These patients usually have some form of impaired immunity. Major risk factors for reactivation of tuberculosis include:

- HIV infection

- Close contact with an infectious patient

- Receiving an organ transplant

- Chronic renal failure requiring dialysis

- Treatment with TNF-alpha blockers

- Silicosis

Post-primary tuberculosis

Post-primary tuberculosis, also known as reactivation tuberculosis, usually occurs a year or two after the primary infection. Reactivation often occurs in the setting of a decreased immune status and commonly involves the lung apex. It can affect all organs and body systems. The presentation of post-primary tuberculosis is highly variable.

Pulmonary tuberculosis is the most common presentation, accounting for 60% of cases in the UK. General symptoms are common and include fever, night sweats, weight loss, anorexia and malaise. Patients commonly have a chronic, productive cough and/or haemoptysis. It can result in pneumonia, lobar collapse, bronchiectasis and pleural effusion.

Extrapulmonary tuberculosis is more common in children and the immunosuppressed. Around 15-20% of cases spread to extrapulmonary sites such as the pleura, central nervous system, lymphatics, bones, joints, and genitourinary system:

- Genitourinary tuberculosis is the most common site outside the lungs and often presents with ‘sterile’ pyuria. It can also cause salpingitis, abscesses, renal lesions and infertility in women.

- Pott’s disease is extrapulmonary tuberculosis that affects the spine. It primarily affects the lower thoracic and upper lumbar vertebrae. It can also affect other parts of the musculoskeletal system, causing isolated bone and joint lesions.

- Scrofula refers to cervical tuberculous lymphadenopathy. Scrofula is also referred to as a cold abscess due to the absence of erythema and warmth.

- Skin lesions can occur, most commonly erythema nodosum and erythema induratum.

- Miliary tuberculosis (disseminated tuberculosis) refers to tuberculosis that has widely disseminated to other organs via blood or lymphatics.

Investigations

Patients with suspected active tuberculosis should be investigated with an initial chest X-ray and microbiological samples.

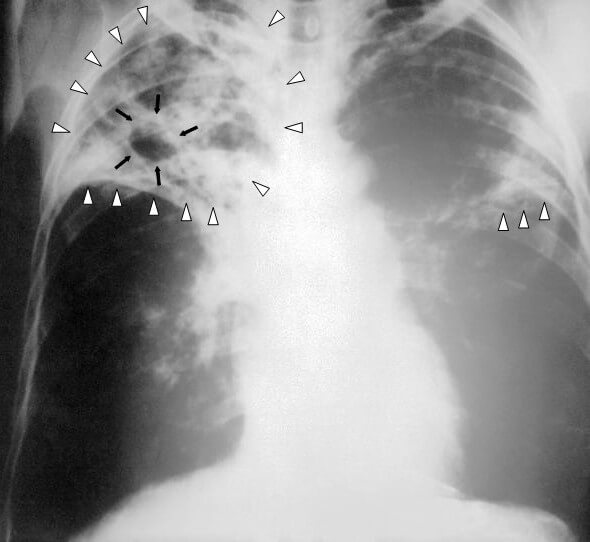

There are five main patterns of pulmonary tuberculosis seen on chest X-ray:

- Parenchymal disease (usually as dense, homogenous parenchymal consolidation, most commonly in the lower and middle lobes)

- Galaxy sign (clustered parenchymal opacification)

- Miliary opacities

- Pleural effusion

- Lymphadenopathy

A calcified radiological scar called the Ghon focus persists in around 15% of cases.

It represents a calcified caseating granuloma. It typically appears in the middle-third of the lung (the lower part of the upper lobe or upper part of the lower lobe).

An AP chest X-ray of a patient advanced bilateral pulmonary tuberculosis, showing bilateral pulmonary infiltrates (white triangles) and cavity formation (black arrows) in the right apical region.

The microbiological investigation for suspected pulmonary tuberculosis is as follows:

- Send at least three spontaneous sputum samples for culture and microscopy

- If this is not possible, consider bronchoscopy and lavage

- The samples should be taken before treatment is started.

For diagnosis, specimens are stained using the Ziehl-Neelson stain and then cultured using the Lowenstein-Jenson medium to suppress other organisms. On microscopy, Mycobacteria tuberculosis is characterised by caseating granulomas containing Langhans giant cells, which have a ‘horseshoe’ pattern of nuclei. The organisms can be recognised by their red colour on acid-fast staining (acid-fast bacilli).

Sputum culture supports the diagnosis of tuberculosis, is more sensitive than smear staining, facilitates identification of the Mycobacterium species by nucleic acid hybridisation or amplification, and evaluates drug sensitivity. Culture on the Lowenstein-Jenson medium typically takes 4-6 weeks.

Mycobacteria tuberculosis can be more rapidly identified using nucleic acid amplification testing (NAAT). NAAT should be performed on at least one respiratory specimen when a diagnosis of tuberculosis is being considered. NAAT may speed the diagnosis in smear-negative cases and may be helpful to differentiate non-tuberculous mycobacteria when sputum is acid-fast smear-positive but NAAT negative.

Genotyping can be helpful in outbreaks of tuberculosis to identify transmission, especially when contact had not been appreciated in the course of epidemiological investigations. Mycobacteria tuberculosis can be typed by a restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) method.

It is also recommended that all patients who have tuberculosis should be tested for HIV within two months of diagnosis. The co-epidemic of tuberculosis and HIV is one of the major global health challenges in the present time. The WHO reported 9.2 million new tuberculosis cases in 2006, of whom 7.7% were co-infected with HIV. Tuberculosis is the most common contagious infection in HIV-immunocompromised patients leading to death.

Treatment

Tuberculosis is treated in two phases, an initial phase using four drugs and a continuation phase using two drugs, in fully sensitive cases. The management of tuberculosis should be under specialist care by clinicians with training in and experience in the specialised care of individuals with tuberculosis.

The initial phase lasts two months, and the treatment combination of choice is isoniazid, rifampicin, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol. Streptomycin is rarely used in the UK but may be used as an alternative treatment in the initial phase of treatment if resistance to isoniazid has been established before treatment is commenced.

The continuation phase usually lasts four months, and the combination of choice is isoniazid and rifampicin. Longer treatment for ten months should be offered in individuals with active tuberculosis of the central nervous system, with or without spinal involvement. Treatment should be modified according to drug susceptibility testing.

Treatment should be started without waiting for culture results if clinical signs and symptoms are consistent with a tuberculosis diagnosis; consider completing the standard treatment even if subsequent culture results are negative.

Within the UK, there are two regimens recommended for the treatment of tuberculosis: unsupervised or supervised. The choice of either regimen is dependent on a risk assessment to identify if an individual needs enhanced case management.

Screening

Approximately 1/3 of the world’s population has latent tuberculosis infection. In the UK, the routine administration of the BCG vaccination to all children was discontinued in 2005 and has now been replaced by a tuberculosis risk-based programme called active case finding (ACF). The only vaccine currently available is Bacillus Calmette-Guerin (BCG).

ACF is a strategy to identify and treat people with tuberculosis who would otherwise not seek prompt medical care and targets the following high-risk groups:

- Professionals at risk of tuberculosis, e.g. healthcare workers

- Close contacts of patients with active tuberculosis

- Immunocompromised patients, e.g. those with HIV

- Homeless people

- Prisoners

- People with drug and/or alcohol problems

- Immigrants from countries where tuberculosis is common

The Heaf test was used as the tuberculosis screening test in the UK prior to 2005. It involves the injection of 100,000 units/ml of tuberculin purified protein derivative into the skin using a multi-pointed ‘Heaf’ or ‘Sterneedle’ gun. The reading of the Heaf test is defined by a scale. Greater than 10 mm of induration is regarded as a strongly positive result.

The Mantoux test replaced the Heaf test as the tuberculosis screening test in the UK in 2005. It involves the injection of 5 Tuberculin units (0.1 mL) intradermally. The result is read 2-3 days later and interpreted as follows:

- Mantoux negative – Induration less than 6 mm

- Mantoux positive – Induration 6 mm or greater

- Mantoux strongly positive – Induration 15 mm or greater

Both tuberculin skin tests are classic examples of type IV hypersensitivity reactions.

Header image used on licence from Shutterstock

Thank you to the joint editorial team of www.mrcemexamprep.net for this ‘Exam Tips’ post.

Great effort! Thank you.