The Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS) program was introduced in the 1980s to address the need for higher-quality trauma care, particularly in the “first hour” after injury, following an incident in which an orthopaedic surgeon crashed his plane in a rural setting. The surgeon sustained serious injuries, three of his children sustained critical injuries, and one child sustained minor injuries. Sadly, his wife died instantly in the crash. He felt that the care that he and his family received was sub-standard, stating at the time:

“When I can provide better care in the field with limited resources than what my children and I received at the primary care facility, there is something wrong with this system, and the system has to be changed.”

This led to the development of the ATLS program that is so widely attended around the world today. Over the past 40 years or so, the program has grown in scope and is now taught in 86 different countries, with well over 1 million students having completed the course.

The ATLS program recently released its 10th edition, which contains several key changes based upon recent literature updates. The main changes are highlighted in this article on a chapter-by-chapter basis.

Initial assessment

No major changes have been made to the traditional ABCDE approach to the assessment of the trauma patient, and ATLS continues to support prioritising the rapid assessment and treatment of life-threatening airway and breathing problems ahead of circulatory issues.

ATLS now recommends that only 1 L of crystalloid fluid is provided during the initial assessment, and that blood products are moved on to quickly in patients that do not respond to the crystalloid.

Airway and ventilation

The nature and methodology of the rapid assessment of the airway remain unchanged. Drug-assisted intubation has now replaced rapid sequence intubation (RSI) as the broad term that describes the use of drugs to assist intubation and the intubation process itself in trauma patients with intact gag reflexes. Videolaryngoscopy has also been highlighted for its usefulness in trauma patients requiring definitive airways.

Shock

The infusion of greater than 1.5 L of crystalloid has been shown to be associated with increased mortality in trauma. For this reason, the early use of blood products is advocated, and there is no place for the infusion of large volumes of crystalloid fluid in trauma patients. Massive transfusion should be utilised if needed and is defined as the transfusion of more than 10 units of blood in 24 hours, or more than four units of blood in one hour. Early resuscitation with blood and blood products in low ratios is recommended in patients with evidence of Class III and IV haemorrhage.

Following the results of several important trials, including the landmark CRASH-2 study, tranexamic acid is now recommended within 3 hours at a loading dose of 1 g IV over 10 minutes, followed by 1 g infused over eight hours. In some areas, tranexamic acid is also being used in the pre-hospital setting.

Thoracic trauma

The life-threatening thoracic injuries have been modified, flail chest being replaced by tracheobronchial tree injury. The life-threatening thoracic injuries are now:

- Airway obstruction

- Tracheobronchial tree injury

- Tension pneumothorax

- Open pneumothorax

- Massive haemothorax

- Cardiac tamponade

Traditionally needle thoracocentesis has been performed by inserting a large-bore needle or cannula into the 2nd intercostal space in the mid-clavicular line of the affected hemithorax. Cadaver studies, however, have shown improved success in reaching the thoracic cavity when the 4th or 5th intercostal space in the mid-axillary line is used instead of the 2nd intercostal space in the mid-clavicular line in adult patients. ATLS now recommends this location for needle decompression in adult patients. The location in children remains unchanged, and the 2nd intercostal space in the midclavicular line should still be used. Needle thoracocentesis is a temporising measure only, and definitive treatment remains the insertion of a chest drain.

The focused abdominal sonography for trauma (FAST) technique has been modified to include an evaluation of the thoracic cavity for the presence of air, which can aid in the rapid diagnosis of pneumothorax.

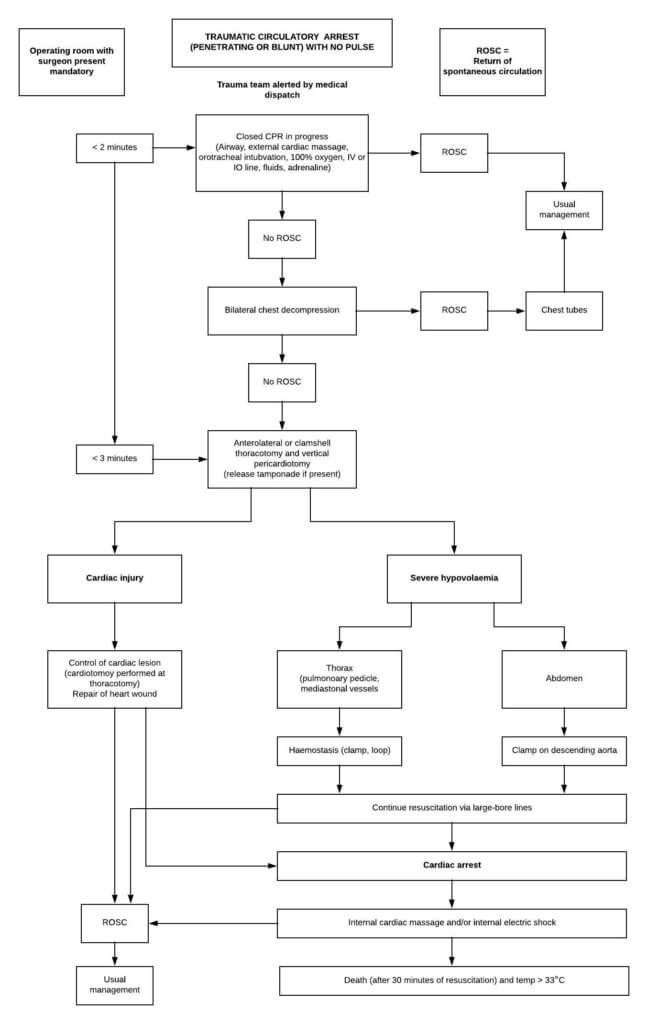

Traumatic circulatory arrest algorithm

A new algorithm outlining the management of patients presenting in traumatic circulatory arrest is also included in the thoracic trauma chapter. This algorithm is shown below:

Abdominal and pelvic trauma

A high-riding prostate on digital rectal examination has traditionally been included as part of the evaluation or urethra and bladder injury. This is no longer considered an accurate or useful determiner and is no longer recommended.

Recent success using preperitoneal pelvic packing in patients with haemodynamic instability due to severe pelvic fractures has led to its inclusion in the management of haemorrhage algorithm.

Head trauma

Elderly patients that are anticoagulated are becoming an increasingly large trauma patient demographic. In view of this, an anticoagulation reversal table is now included in the guidance.

A revised version of the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) has been introduced, the scale remains the same, but there has been clarification added for the terms used, and the importance of reporting the numerical components of the score is stressed. A new designation, NT (not testable), has also been added and should be used when a component of the score cannot be assessed.

More detailed guidance on systolic blood pressure management and seizure prophylaxis is now also included.

Spine and spinal cord trauma

Determining which patients require imaging to evaluate for spine and spinal cord injury can be challenging in the trauma setting. Because of this, the Canadian Cervical-Spine Rule (CCR) and the National Emergency X-Radiography Utilization Study (NEXUS) guidelines are now recommended to be used in the decision-making process.

The term “spinal immobilisation,” should no longer be used, and has been replaced with “spinal motion restriction.” Prolonged backboard usage (> 2hours) should be avoided to reduce the risk of skin ulcer formation.

Musculoskeletal trauma

The use of a tourniquet to control severe extremity bleeding is now recommended.

Antibiotics used to treat open fractures should be dosed based on the patient’s weight to ensure adequate tissue levels are achieved, and regimens are provided.

Thermal injuries

Fluid resuscitation in burns has been adjusted to mirror the changes in trauma fluid resuscitation. Adult patients with deep-partial and full-thickness burns involving more than 20% total body surface area (TBSA) should receive initial fluid resuscitation of 2 ml/kg/%TBSA. In paediatric burns 3 ml/kg/%TBSA should be used, and 4 ml/kg/%TBSA used for electrical burns.

The first half of the fluid should be given over the course of eight hours, and the remaining half is provided over a span of 16 hours. The rate of fluid administration should be titrated to effect using a target urine output of 0.5 ml/kg/hr in adults or 1 ml/kg/hr in children who are hemodynamically normal. Fluid boluses should be reserved for use in unstable patients only.

Paediatric trauma

The PECARN traumatic brain injury algorithm, which was derived from the multicentre PECARN network is now recommended as a clinical decision rule to identify children at risk of traumatic brain injury and help guide the decision to undertake a CT head.

Geriatric trauma

A lower threshold for imaging in the elderly population is now recommended. Five pre-existing conditions are highlighted as posing a twofold risk for trauma mortality, and candidates are made aware of these:

- Cirrhosis

- Coagulopathy

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- Ischaemic heart disease

- Diabetes mellitus

Pelvic fractures in geriatric patients result in a greater need for transfusion even with stable patterns of injury. The mortality is 4 times higher with these injuries, hospital stays are longer, and these patients may not return to an independent lifestyle.

Trauma in pregnancy

The main update in this chapter is the recognition that a vaginal fluid pH greater than 4.5 is an indicator of amniotic fluid leakage.

Transfer to definitive care

Performing unnecessary tests in the primary hospital can have a negative impact on patient outcomes. Procedures and tests that do not change the plan of care and CT scans should now be avoided in the primary hospital. The SBAR (situation, background, assessment and recommendations) communication tool is recommended as a means of relaying useful information between centres.

SUMMARY TABLE

| Chapter | New recommendations |

|---|---|

| Initial assessment | Restriction to only 1 L of crystalloid fluid during initial assessment. |

| Airway & ventilation | Drug-assisted intubation has now replaced rapid sequence intubation (RSI). Videolaryngoscopy highlighted as useful. |

| Shock | Early use of blood products advocated. Tranexamic acid is now recommended within 3 hours. |

| Thoracic trauma | Flail chest replaced by tracheobronchial tree injury as a life-threatening injury. New location for needle thoracocentesis in adults Modified FAST recommended for identification of pneumothorax. Traumatic circulatory arrest algorithm introduced. |

| Abdominal & pelvic trauma | Prostate examination no longer recommended as part of the evaluation. Preperitoneal pelvic packing included in haemorrhage protocol. |

| Head trauma | Anticoagulation reversal table is now included in the guidance. Revised version of the GCS introduced. |

| Spine & spinal cord trauma | CCR and NEXUS guidelines are now recommended. “Spinal immobilisation” has been replaced with “spinal motion restriction.” Prolonged backboard usage (>2 hours) should be avoided. |

| Musculoskeletal trauma | The use of a tourniquet to control severe extremity bleeding is now recommended. Antibiotics dosing regimens for open fractures introduced. |

| Thermal injuries | New fluid resuscitation formula (2 ml/kg/%TBSA) |

| Paediatric trauma | The PECARN traumatic brain injury algorithm now recommended. |

| Geriatric trauma | Lower threshold for imaging in the elderly population is now recommended. High-risk pre-existing conditions highlighted. |

| Trauma in pregnancy | Vaginal fluid pH greater than 4.5 is an indicator of amniotic fluid leakage. |

| Transfer to definitive care | CT scans should now be avoided in the primary hospital. SBAR communication tool now recommended. |

Thank you to the joint editorial team of www.frcemexamprep.co.uk for this article.

Header image used on licence from Shutterstock

Thanks for the info

Many thanks

Gracias por la información. Son valiosos su aportes.

Thank you for the update

Thank you for the update

Thanks for the update.

Thanks for the update

Thanks for the update

Thank you so much 😊

I will love get more information

The first ATLS course was held in Indonesia in March 1995, with the help of Instructors from USA and Australia

The way of thinking of ATLS concept is useful, it can be applied for other field instead of surgeon ( my field is Neurosurgeon) and also every physician as a provider in emergency cases especially in trauma

Since 1995 until 2023 ( except during pandemi Covid-19) ATLS course still interested by mopst physician

Our problems is we still have difficulties in delivering competencies to the emergency physician, like Oro-tracheal intubation, cricothyroidotomy, insertion of chest tube and other invasive procedure for resuscitation

Fortunately there are several key changes from 8 to 10 edition, like introduction of LMA, chest decompresion site in adults

Thank you for always have a new key changes based on recent literatur